This is part of a series on Hungarian foods – three main courses, three desserts. This is the second main dish, following stuffed cabbage.

Rakott Krumpli is not the name of a man in a folktale, it is a food. And if I were to predict, I would say that while stuffed cabbage won’t make it to the next generation of my family, Rakott Krumpli most certainly will. When I think of Rakott Krumpli, I think of sitting around the kitchen table with my parents and my sister, a tall, steaming casserole of the dish at the center. And I think of sitting around the kitchen table with my wife and my son and daughter, a tall, steaming casserole of Rakott Krumpli at the center. It is a dish for chilly fall and winter nights, when eating rich dishes in warm kitchens with family is a happy impulse, and then a pleasant habit, and then indelible upon the memory.

For sure, there are lots of potatoes in Rakott Krumpli, and they are layered, along with sliced hard-boiled egg, sour cream, and Hungarian sausage. But don’t call Rakott Krumpli layered potatoes. Call it Rakott Krumpli (RAH-cut CROOM-plea). Certain things are just certain things.

Mixing Like The Many Cultures Of The Greater Hungary Of Long Ago

It is an earthy dish of simple ingredients. But the beauty of Rakott Krumpli lies not in its simplicity, it is in its three dimensionality. The transition from mere layer to layering. gives the dish its drama, its creativity. Put some butter at the bottom, then sliced boiled potatoes, then sliced hard-boiled egg, then generous dollops of sour cream, then spicy Hungarian sausage, then salt and paprika. Then again: potato, egg, sour cream, sausage. And again: potato, egg, sour cream, sausage.

I have seen recipes that suggest using a low-sided baking dish. No! Definitely not. For layering, you’ll need a deep casserole. It might take a little longer time in the oven to get the sizzly simmering music that says it’s ready, but layering is a must. One of the great delights of Rakott Krumpli is plunging down through all the layers with a big, wide serving spoon. Moussaka? Lasagna? They give nothing like the pleasure of digging into Rakott Krumpli. They are too thin, too docile. Rakott Krumpli puts up a palpable resistance as you press the serving spoon through each layer of potato. You can feel the personality of the food, not simply see or taste it.

Another great delight is its disorder. When you make it, and when you have a hunk of Rakott Krumpli in the serving spoon, it is a rational set of layers, but then when you put it on your plate, it tips and sprawls. It is meant to sprawl and mix, that this is part of its inner nature. One might say the tipping is like the Hungarian impulse toward creativity, and that the mixing is representative of the many cultures of the greater Hungary of years ago.

Your Heart Leaps

A third pleasure is its addictive quality. As you finish a serving, you might see that you are down to your last sausage. And so you plunge the spoon back into the casserole to carve off a slice, and opportunistically scoop up few pieces of sausage that may lay about in the dish. And then a few minutes later, oh my, you may notice that you have only a little potato left, and wouldn’t it be nice to have a little more to go with the extra sausage on your plate? In goes the serving spoon again. It is a dish that somehow keeps replenishing itself on your plate, and it takes an extra exertion of reason, or a very full belly, to rein in this happy conspiracy of mind and stomach.

A final pleasure may come a day or two later. You may find that no one else is home that evening, and that you have no idea what to make yourself for dinner. And as you poke through the fridge your heart leaps as you discover the last Rakott Krumpli leftovers. You are happy not simply because you don’t have to cook something from scratch, but because you know what awaits. Over the last couple of days the flavors have marinated further, making the dish even more flavorful. And you know when you re-heat it in that cast iron pot the potatoes, and maybe the egg slices such as they may have held together, will get a little browned and crispy, and now there is a new texture that makes it even more of a treat.

As P.T. Barnum Said

And then the climactic tragedy as you stand there scraping the last crispy remnants from the pot with a spatula, wiping them onto your finger and into your mouth. And then it is gone. But I think the final delight of this carnival of flavor is that, as P.T. Barnum is reputed to have said of the goal of other entertainments, it always leaves you wanting more.

Buy the book, Finding Maria (Bloomingdale Press – 2nd edition November 25, 2019), on Amazon

Recipe

Posted on Categories Findings, Hungary

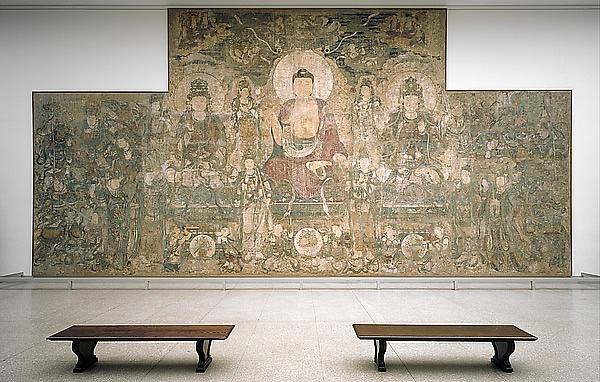

[This is the first in a series of posts on Hungarian foods.] Stuffed cabbage was a dish I picked at as a child, and over time it sank into the deepest recesses of my mind. I’d surely never eat it again. But one evening in my early thirties it rose to the surface, bringing with it something of the past. I was living and working in central Connecticut. I changed apartments after the first year, looking to save on rent. The new building was small, old and more than a little run-down. The building had a name, Hy-up, written in concrete on the side of the structure. The ground floor was occupied by a young couple who fought late into the night. One day they were evicted by force. The owner lived on the top floor. He had a glass eye, the result of a bad motorcycle accident, was often a little drunk, and kept a shotgun in the corner of the main room of his place. He was gruff, but he took a liking to me, and sometimes, to break up a long, quiet weekend, I stopped up to say hello. The wattage was low, the floors creaky, and the wooden staircase that led from the outside to my third-floor entrance groaned from the effort of holding me up. But the view offered a measure of relief. The building was set into a hillside, and I spent many evenings in a chair in my bedroom, looking out over athletic fields, past the juvenile detention center, at the forest in the distance. One winter, the snow seemed to obscure everything but long days at work and evenings in that chair meditating on the purple-white view. I had been thinking about becoming a vegetarian, and one day, while toying with that idea, I thought, for no apartment reason, I’d make stuffed cabbage for dinner. I loved to cook from intuition, to invent things in the moment. So, I went out and bought some vegetarian sausage (Apologies. I know I’ve just caused heart attacks across Hungary!), a cabbage, canned plum tomatoes, and a few other ingredients. I had no idea how to get the cabbage leaves soft enough to roll. What I did was boil a big pot of water, dunk a whole cabbage in it for a few minutes, take it out, and peel off a few of the softened leaves. Well, it worked anyway. I took a small handful of the “meat”-and-rice mixture I’d made, compressed it into a sort of football shape (American football), rolled it up in a leaf, tucked in the edges, and placed it in a glass baking dish. Then I boiled the cabbage some more. When I had filled the dish, I covered the whole thing in a sauce of broth and chopped tomatoes, and put it in the oven. While the dish cooked, I returned to my window seat. I thought about work and the friends I would see that weekend in New York. I thought about my grandmother, who I had begun to meet-up with occasionally on trips into the city. I had found her to be a warm, interesting, even comforting presence, and had unexpectedly begun to look forward to our visits. My mind wandered to the story she had told me last time about a ride she’d once taken in the side-car of her favorite cousin’s motorcycle. She must have been an adolescent or young teen, and I thought about how hard she had laughed as she recalled how her cousin had sped up near the end of the ride, and how the motorcycle had run off the road at a curve it couldn’t handle, how it had rolled over numerous times. “I was in bed for two weeks!” she had said, her shoulders shaking with laughter, her face turning bright red. “Jaj, it was terrible!” When I was young, my grandmother felt distant to me, with her odd formality, strange accent, and opera-tinted view of the world. Stuffed cabbage embodied the feelings of those early years. It was strange and never grew on me. The sauce, if it could be called that, was runny and weak. Cabbage? Does any food have less flavor and personality than cabbage leaves? And the ground meat and rice combination wrapped inside? It was uninteresting to a young boy. Why not just alter it a little and turn it into meatballs for spaghetti and meatballs? Stuffed cabbage should have vanished from my life. But food forges powerful memories, not only of smells, but of people, relationships, and feelings, and of ourselves at a moment in life. Looking back on that evening now, the connection between the start of those visits with my grandmother and the seemingly spontaneous impulse to cook stuffed cabbage seems pretty clear. The timer went off and I pulled the baking dish out of the oven, served myself, and took a seat at my small round dining table. The stuffed cabbage was delicious. No, really. The spice of the (vegetarian) sausage-rice center, balanced by the soft texture and gentle flavor of the cabbage leaves, together with the tang and moisture of the cooked tomatoes. I froze the leftovers and enjoyed them for weeks. Buy the book, Finding Maria (Bloomingdale Press – 2nd edition November 25, 2019), on Amazon I could not understand my grandmother’s comfort with tragedy – not at the start anyway. “Life in Hungary is terrible. Terrible!” she said, recounting a recent trip to Hungary during one of our weekend lunches in the mid-1990s. “Everything is so expensive now. There are so many political parties, like before the war. Some of them are anti-Semitic.” I was in my early thirties, and, to me, tragedy, or even the risk of tragedy, was still to be avoided at all costs, perhaps even the cost of happiness. As much as she seemed to relish terrible circumstances, she also had a passion for beauty. One afternoon, in a large gallery of the Metropolitan Museum, we sat for a long time in front of a fresco from a wall of a temple in North China from the 1300s. We talked about the piece as I referred to an information card to explain the various Buddhist figures. “And who are those people there?” she asked, gesturing toward the top of the wall. “Jaj!” she said in response to my answer, slapping one of her cheeks. She searched the fresco as if in a trance, her face calm but for the slightly upturned corner of her mouth. “It is possible always to discover new things,” she said. “Wonderful.” I had not wanted to spend time with her, resisted playing the dutiful grandson. But after my father’s repeated noodging – “Don’t you get down to New York ever?” he would ask – I phoned her to invite her to lunch. Just one call, I thought at the time, there won’t be anything more to it. But there was. Over several years of these afternoon visits we became friends – not as child and grandparent, but adults. There were stories about her special cousins, Simon and István. Simon was her favorite. She told me about the time he had offered her a ride in his sidecar. Just before the ride ended, he took a curve a bit too fast and the motorcycle rolled over multiple times. “I was in bed for weeks!” she exclaimed. “Jaj, it was terrible!” But as she said this, her shoulders shook with laughter and her face turned red with overflowing joy. A terrible accident, but a beautiful moment. The same afternoon that she recalled this story, as we strolled down Central Park West after a film, she told me about his death. “The doctor warned him to stop smoking, and he did. But it was too late. Two months later a cousin stopped by the store, a good customer, and they were telling jokes to each other. In the middle of a sentence he fainted. At the hospital, the doctor met me outside the room and told me it was a massive brain hemorrhage. There was nothing they could do.” Another time, as we walked slowly down Park Avenue near the 92nd Street Y, I learned about poor Aunt Jolan, who lost a son in World War I and was left a vegetable at the end of her life. Half a block later she told me about how Simon and István, who looked like twins, had fooled a barber into thinking he had done such a poor job shaving István’s beard that it had grown right back. She laughed herself to tears as she finished. There they were again, tragedy and beauty. They were woven into the fabric of her life. Almost unconsciously, something in the closeness to her repeated examples, something in her life force, a force that seemed fueled by both tragedy and beauty, affected me. The visits with her coincided with a time of uncertainty about major aspects of my life: love and work. As I look back on it now, this uncertainty seems really to have been fear – fear of making wrong decisions, fear of pain and wasted life-time, fear of tragedy. During the time when she and I grew close, somehow I began to make sense of my fears, and eventually, almost without notice, a kind of fusion occurred. I accepted the necessity, the richness, of tragedy, the full energy of beauty, and how each reinforced the precious experience and meaning of the other. I took both tragedy and beauty into who I was. What had once seemed strange became my own. I was able to move on. Reflecting on this change, I see how it was more a beginning than an end, really, a kind of passage into adulthood. She died not many years later. Still, every now and then, when I encounter something that has that savory blend of beauty and tragedy, with maybe just a bit of irony or humor mixed in, I can hear her shout, “Jaj! Terrible!” in between laughter-soaked breaths. Buy the book, Finding Maria (Bloomingdale Press – 2nd edition November 25, 2019), on Amazon “March 19, 1944. I never forget that day,” my grandmother told me. She spoke in that particular Hungarian accent, with its often-compressed phrases and odd-sounding emphasis on early syllables. “NEVerforget” began with an exclamation and a shake of the head. On that date, the German army occupied its ally Hungary, at the invitation of Hungary’s leaders. On that date the game was up. Hungary had been divided between more rabid anti-Semites and a ruling class of noblemen whose anti-Semitism (particularly for countryside, lower-class Jews, as opposed to the wealthy Jewish landowners or industrialists they knew personally) was counterbalanced by a quaint if inconsistent sense of honor. Humiliated by the hated Trianon treaty after World War I, under which Hungary lost two-thirds of its territory, as World War II dawned, Hungary dreamed of regaining past glory (or at least lands). It allied itself with Germany, and doubled its territory with spoils from German victories as rewards for major anti-Jewish laws passed between 1938 and 1941. Germany pressed for more, for deportation. Yet the Hungarians put off such action, offering up further discriminatory measures. Wrote Joseph Goebbels in his diary in the spring of 1943, “The Jewish question is being solved least satisfactorily by the Hungarians.” His point is illustrated by the fact that as Goebbels wrote my Jewish grandfather was still running his fabric store in Budapest. My grandfather died on April 9th of that year of natural causes. (A cousin had stopped by the store and to share a joke. My grandfather was smoking a cigarette and laughing at the joke when he was struck by a fatal brain hemorrhage.) In late April 1943, Hungary’s leader, Admiral Miklos Horthy (“We used to have a navy!” my grandmother would declare proudly) met with Hitler and demurred again in the face of Hitler’s demand for the Jews. By early 1944 the Hungarians were looking for a way out and sent peace feelers to the western powers. Worried about the commitment of its ally and the security of Hungary’s oil reserves, angered by the peace feelers and Hungary’s relative inaction on the Jews, Hitler demanded, and Horthy agreed to, occupation by Germany. Many Hungarian leaders felt as Pal Taleki, the prime minister who committed suicide in 1941 after the invasion of Yugoslavia. His suicide note read in part: “We have become breakers of our word…. I have allowed the nation’s honor to be lost. The Yugoslav nation are our friends…. But now, out of cowardice, we have allied ourselves with scoundrels.” And yet, many, including ordinary Hungarian citizens, welcomed the occupation. “A day in Yugoslavia was more dangerous than a year in Hungary,” observed Edmund Veesenmayer, Hitler’s plenipotentiary in Hungary. March 19, 1944. Adolph Eichmann, Nazi engineer of the Holocaust, arrived in Hungary with just a dozen officers and 200 to 300 Sonderkommando, and set to work at the destruction of Hungarian Jewry with newly appointed Hungarian Interior Ministry deputy for administration László Endre. (Eichmann once said of Endre that he “wanted to eat Jews with paprika.”) The Hungarian national police force, the Gendarmerie, was placed at Eichmann’s disposal. Commented one history, “the overwhelming majority of local, district, and county officials, including the civil servants and law enforcement officers, collaborated fully, and many quite enthusiastically.” This date found my father in a Jesuit boarding school in Kalocsa in southern Hungary, donning a uniform in the Papal colors each morning before chapel, only vaguely aware of his Jewish origins under the thick layer of identity formed by his Catholic upbringing. Upon his arrival there in the fall of 1943, he registered with the local police, as traditionally required, writing “Israelite” where the form asked for his parents’ religion. In late March of 1944, his uncle came to return him to Budapest, and to inform him that he would have to wear a Jewish star. By March 19, 1944, three million Polish Jews, a million Jews in Soviet Ukraine, and hundreds of thousands of Jews in other countries had been murdered. In light of this stark context, it still shocks one to think that into the early spring of 1944 the Hungarian Jewish community of some 800,000 remained largely intact. And yet, in a matter of weeks, the Jews of Hungary were concentrated in their villages, towns, and small cities, and on May 15th deportation began in force. Each day, trains carried off some 12,000 men, women, and children. By early July, some 450,000 Hungarian Jews had been sent to Auschwitz. (Anticipating their arrival, the Germans had spent the spring overhauling and expanding the crematoria, unloading ramps, and staffing there.) A sizeable proportion of all the Jews murdered at Auschwitz were killed in just a matter of weeks in the late spring of 1944. Hungary had been emptied of its Jews, except for Budapest, which held the largest remaining intact community in Nazi-occupied Europe. My grandmother obtained false papers, and through cunning, fearlessness, and luck, managed to bring herself and her children through the horror and the hell of both Nazi and Hungarian Nazi terror, and the building-to-building battle the Soviets and Germans fought for Budapest in the winter of 1944-45. Looking back on this history, it is impossible not to see March 19, 1944 as a fulcrum. Before this date, the fate of the Jewish people, the character of the Hungarian nation tipped toward one direction. Upon this date, it balanced decisively, tragically, toward another. The Politics of Genocide: The Holocaust in Hungary, Randolph L. Braham (condensed edition) Buy the book, Finding Maria (Bloomingdale Press – 2nd edition November 25, 2019), on AmazonStuffed Cabbage Should Have Vanished From My Life

He Kept A Shotgun In The Corner

I Had No Idea How To Get Cabbage Leaves Soft

Tang And Moisture

Beauty & Tragedy

Avoided At All Costs

Woven Into the Fabric of Her Life

She told me about her engagement and early years with her first husband (my grandfather), the great love of her life. He was a factory manager, she an administrative assistant. They dated. And then one afternoon as they strolled along the Fisherman’s Walk in the Buda hills overlooking Pest, he told her he was being transferred to Brussels. They stopped at the Ruszwurm, one of the city’s great coffee houses. There, he asked her to marry him. Brussels was a dream. “On weekends we went to Paris, to Amsterdam, to Germany. It was a year I will never forget. Never,” she said, half in a dream.

She told me about her engagement and early years with her first husband (my grandfather), the great love of her life. He was a factory manager, she an administrative assistant. They dated. And then one afternoon as they strolled along the Fisherman’s Walk in the Buda hills overlooking Pest, he told her he was being transferred to Brussels. They stopped at the Ruszwurm, one of the city’s great coffee houses. There, he asked her to marry him. Brussels was a dream. “On weekends we went to Paris, to Amsterdam, to Germany. It was a year I will never forget. Never,” she said, half in a dream.What Had Once Seemed Strange Became My Own

March 19, 1944

Game up

‘We have allied ourselves with scoundrels’

Swift destruction

Character in the balance

Sources:

The Holocaust in Hungary: Forty Years Later, Randolph L. Braham and Bela Vago, eds.

Hungary at War, Cecil Eby