[My series on Hungarian food continues with a final main course…]

If there was a royal dish in our home it was Chicken Paprika. It was the most elevated, the most beloved dish. It possessed its own distinct pageantry. It was rich. We over-indulged in it.

The royalty of Chicken Paprika has a special earthiness to it. Plates were sometimes licked. Leftovers were retrieved from the refrigerator at all hours, for days. I think this earthiness has to do with its Central European origins, a place where high and low culture sometimes mix with an ease not found to the same degree in Western Europe. My father used to say that chicken was rare in Budapest, considered a kind of luxury. This might be one aspect of the highness of the dish. And yet the simplicity of Chicken Paprika gives it a kind populist accessibility. Anyone can make it, and at our house, everyone did.

Nokedli – Among The Most Beautiful of Foods

My mother’s specialties were the chicken and the gravy. After lightly browning the onions, my mother would add chicken to the pot – thighs, legs, breasts – and sear it on both sides. She would shake paprika all across the large, deep, oval pot, add a splash of water, and cover it. Later, if she were visiting at the time, my grandmother would be called in to gauge progress, sticking her face almost into the pot, inhaling the tomatoey peppery aroma deeply several times. “Ah, ya,” she might conclude with a nod, a serious expression on her face (this was serious business), and her approval would energize the foot-soldiers for the rest of the preparations.

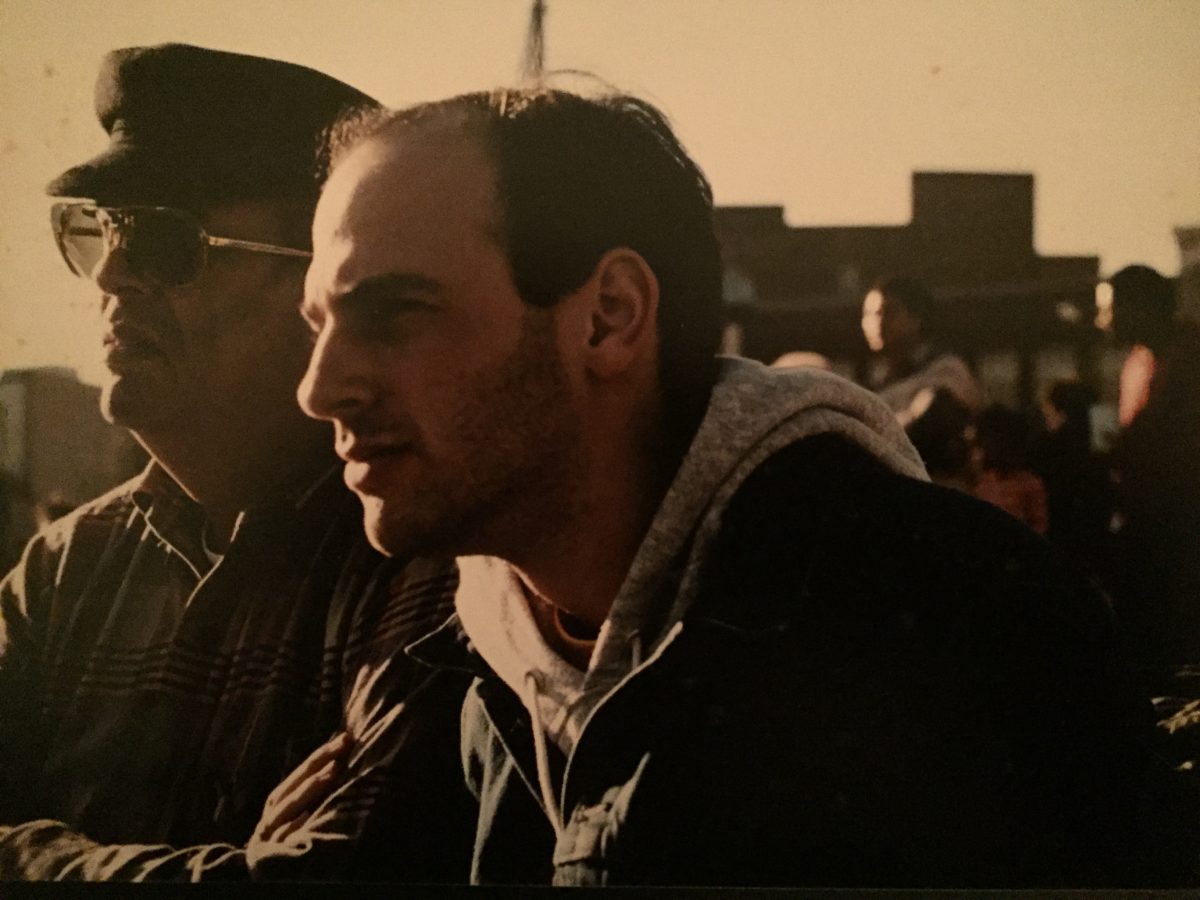

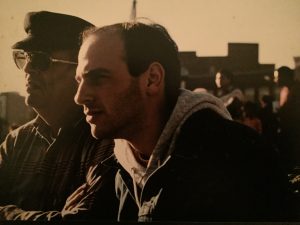

But of course chicken paprika is not Chicken Paprika without Nokedli. This was my father’s province. I picture him in old khakis and a white undershirt (occasionally there would be a nice button-down, as in the picture below), holding a metal bowl tight against his belly while beating the dough vigorously with a wooden spoon, grunting occasionally from the effort. When the dough was ready, my father would spoon a large clump onto a cutting board. Now came the tricky part, the part that required both artfulness and technical skill. My father would take a large, sharp knife and restructure the clump of dough into a log. Then with the knife, he would separate a long slice from the log, maybe a half inch or so thick. And finally, holding the end of the cutting board over a big pot of boiling water, he would, in one motion, cut an inch or so from the slice, slide it gracefully into the pot, and dip the knife in the hot water (so the dough wouldn’t stick when he cut the next piece). He would repeat the motion quickly until the slice was gone, then begin the routine again.

In a few minutes, the dumplings would rise to the surface as if calling to be removed (though they still required 5 to 7 minutes more cooking). One of the happiest sights of my youth (and still to this day) was a casserole dish filling with Nokedli as they were removed from the pot.

Nokedli are one of the most beautiful foods. When they are properly made, that is. A beautiful Nokedli has an irregular silhouette and topography. Each one is similar, yet different – the result of the length cut from the log, the degree to which some may have rubbed off as the knife slid across the cutting board, the position it was in when it hit the scalding water. Too often, Nokedli are thin, small, and scraggly. Maybe these are traditional in someone’s eyes. But a proper Nokedli, in my view, has a certain heft to it, a kind of meatiness in your mouth. It is oblong, not missile shaped. It is from the dumpling family, not the rice or pasta family, so a Nokedli that has the diameter on its narrow dimension of spaghetti is not Nokedli. The diameter of a pencil? No. Should be a half-inch, even three-quarters. And at least an inch long. Now, not too big. We’re not talking pierogi-sized here. Two or three in your mouth at a time. Not a dozen. Not just one.

They Become One

Near the end of the cooking process, when the Nokedli were finished and the chicken was done, my mother would make the gravy. Though she was not Magyar (she was from Brooklyn), she was a genius with the gravy. She knew just how much sour cream to add, just how long to simmer it, and she always managed to produce the exquisite taste, which is as much in its texture as its flavor – small squares of onion, odd bits of chicken, tiny globules of sour cream. The gravy unifies the dish. You spoon it generously over the chicken and Nokedli, and they become one.

One last thing is essential to the royalty of Chicken Paprika: Uborka Saláta, Hungarian cucumber salad. Its name is like a primal chant – “OOOborkahSALAta” – so different from the refined notes it adds to the meal. Simplicity is part of its genius – cucumber sliced paper thin, a touch of sour cream, a little vinegar, some paprika. It is a side dish, not a centerpiece, served best quite literally to the side in a small bowl. Uborka Saláta is the light and fresh complement to the rich and exuberant Chicken Paprika. Alternating them every now and then substantially increases the flavors and pleasure of a Chicken Paprika meal.

A Slap Of The Table Top

When the words “home” and “special occasion” are mentioned together, an image comes to mind. In the center is a plate, one half is filled with chicken breast meat and maybe a whole thigh, the other half with a crowded herd of Nokedli. Everything is coated with the orange-brown gravy. At the top of the plate, which could just as easily be everyday china as Limoges china, to the left, is Uborka Saláta in a small glass bowl. To the right, a cup of water, or, when I was older, a glass of wine. Perhaps it is Hungarian wine. And perhaps at the end of his usual toast my father might have chosen to conclude, on this night, “Egészségedre!” Adding, in a stage whisper to us, “That means ‘to your health.’ But be careful not to pronounce it as ‘A seggedhez’!” punctuating the laugh that followed with a slap of the table top.

You can buy the book, Finding Maria (Chickadee Prince Books, 2017), now on Amazon