Avoided At All Costs

I could not understand my grandmother’s comfort with tragedy – not at the start anyway. “Life in Hungary is terrible. Terrible!” she said, recounting a recent trip to Hungary during one of our weekend lunches in the mid-1990s. “Everything is so expensive now. There are so many political parties, like before the war. Some of them are anti-Semitic.” I was in my early thirties, and, to me, tragedy, or even the risk of tragedy, was still to be avoided at all costs, perhaps even the cost of happiness.

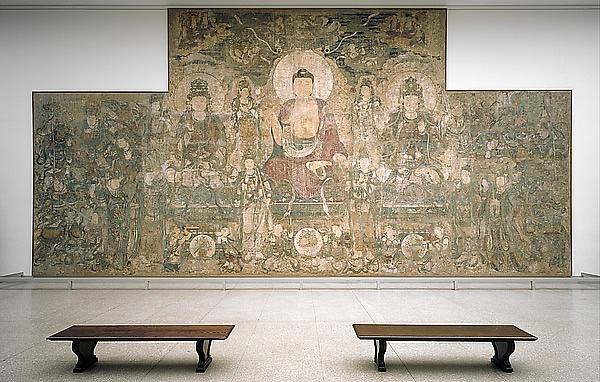

As much as she seemed to relish terrible circumstances, she also had a passion for beauty. One afternoon, in a large gallery of the Metropolitan Museum, we sat for a long time in front of a fresco from a wall of a temple in North China from the 1300s. We talked about the piece as I referred to an information card to explain the various Buddhist figures. “And who are those people there?” she asked, gesturing toward the top of the wall. “Jaj!” she said in response to my answer, slapping one of her cheeks. She searched the fresco as if in a trance, her face calm but for the slightly upturned corner of her mouth. “It is possible always to discover new things,” she said. “Wonderful.”

I had not wanted to spend time with her, resisted playing the dutiful grandson. But after my father’s repeated noodging – “Don’t you get down to New York ever?” he would ask – I phoned her to invite her to lunch. Just one call, I thought at the time, there won’t be anything more to it. But there was. Over several years of these afternoon visits we became friends – not as child and grandparent, but adults.

Woven Into the Fabric of Her Life

There were stories about her special cousins, Simon and István. Simon was her favorite. She told me about the time he had offered her a ride in his sidecar. Just before the ride ended, he took a curve a bit too fast and the motorcycle rolled over multiple times. “I was in bed for weeks!” she exclaimed. “Jaj, it was terrible!” But as she said this, her shoulders shook with laughter and her face turned red with overflowing joy. A terrible accident, but a beautiful moment.

She told me about her engagement and early years with her first husband (my grandfather), the great love of her life. He was a factory manager, she an administrative assistant. They dated. And then one afternoon as they strolled along the Fisherman’s Walk in the Buda hills overlooking Pest, he told her he was being transferred to Brussels. They stopped at the Ruszwurm, one of the city’s great coffee houses. There, he asked her to marry him. Brussels was a dream. “On weekends we went to Paris, to Amsterdam, to Germany. It was a year I will never forget. Never,” she said, half in a dream.

She told me about her engagement and early years with her first husband (my grandfather), the great love of her life. He was a factory manager, she an administrative assistant. They dated. And then one afternoon as they strolled along the Fisherman’s Walk in the Buda hills overlooking Pest, he told her he was being transferred to Brussels. They stopped at the Ruszwurm, one of the city’s great coffee houses. There, he asked her to marry him. Brussels was a dream. “On weekends we went to Paris, to Amsterdam, to Germany. It was a year I will never forget. Never,” she said, half in a dream.

The same afternoon that she recalled this story, as we strolled down Central Park West after a film, she told me about his death. “The doctor warned him to stop smoking, and he did. But it was too late. Two months later a cousin stopped by the store, a good customer, and they were telling jokes to each other. In the middle of a sentence he fainted. At the hospital, the doctor met me outside the room and told me it was a massive brain hemorrhage. There was nothing they could do.”

Another time, as we walked slowly down Park Avenue near the 92nd Street Y, I learned about poor Aunt Jolan, who lost a son in World War I and was left a vegetable at the end of her life. Half a block later she told me about how Simon and István, who looked like twins, had fooled a barber into thinking he had done such a poor job shaving István’s beard that it had grown right back. She laughed herself to tears as she finished.

There they were again, tragedy and beauty. They were woven into the fabric of her life. Almost unconsciously, something in the closeness to her repeated examples, something in her life force, a force that seemed fueled by both tragedy and beauty, affected me.

What Had Once Seemed Strange Became My Own

The visits with her coincided with a time of uncertainty about major aspects of my life: love and work. As I look back on it now, this uncertainty seems really to have been fear – fear of making wrong decisions, fear of pain and wasted life-time, fear of tragedy. During the time when she and I grew close, somehow I began to make sense of my fears, and eventually, almost without notice, a kind of fusion occurred. I accepted the necessity, the richness, of tragedy, the full energy of beauty, and how each reinforced the precious experience and meaning of the other. I took both tragedy and beauty into who I was. What had once seemed strange became my own. I was able to move on. Reflecting on this change, I see how it was more a beginning than an end, really, a kind of passage into adulthood.

She died not many years later. Still, every now and then, when I encounter something that has that savory blend of beauty and tragedy, with maybe just a bit of irony or humor mixed in, I can hear her shout, “Jaj! Terrible!” in between laughter-soaked breaths.

Buy the book, Finding Maria (Bloomingdale Press – 2nd edition November 25, 2019), on Amazon