If there is a major gift in memoir, it is the close exposure it gives a reader to a particular character, or small set of characters, and the ability to watch up close what happens to the author and the other characters in a particular period of time. Yet if there is a major problem in memoir, particularly from the writer’s perspective, it is precisely that in shaping and shaving down the characters to recreate, to produce with vividness, interactions that spark the transformation of those involved, and that give the gift to the reader, the characters must be simplified.

In writing memoir, we draw upon only the set of events and relationships within which the story is set. We may say little about what comes before or after or around the story in the lives of our characters.

Bass Clef, Treble Clef

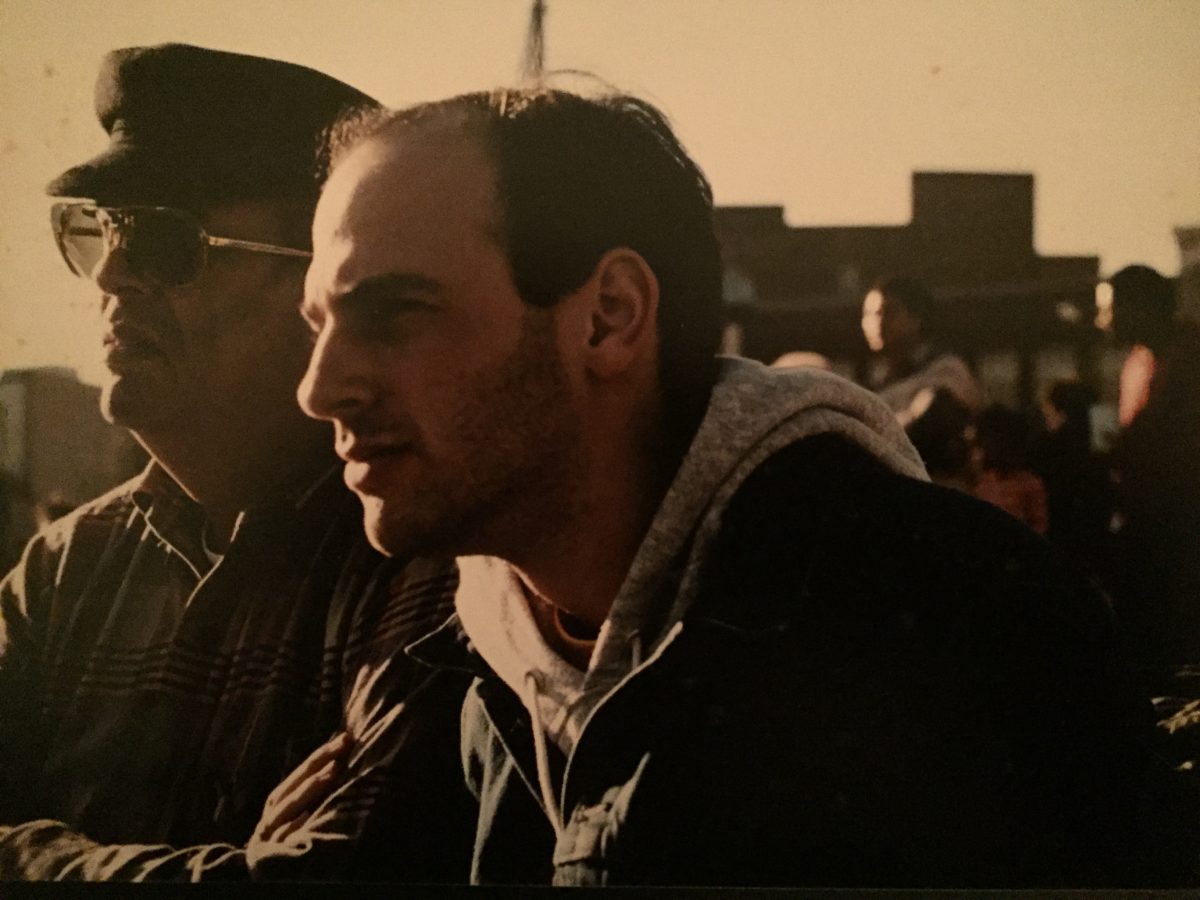

My father plays a prominent supporting role in Finding Maria, the memoir I wrote about my relationship with his mother. An important sub-plot in the book is the story of cleaning out my grandmother’s apartment with my father and my aunt. The primary story of my grandmother and me is enriched by the old sibling tensions that emerge as photos and objects in the apartment trigger my father’s and my aunt’s childhood memories. The idea of the flows of wartime and Holocaust trauma through generations adds further dimension, and is brought to life by my father’s struggles to reach his memories, and by my frustration with the paucity of contact with his past he afforded me growing up. His melancholy at its mention paints a deep picture of his mother’s troubled relationship with her second husband, deeper even than the few memories of it he was willing to share.

The clean-out is the bass clef to the treble clef of the grandmother-grandson story. It adds breadth and nuance to Maria. But including the clean-out story comes with a cost. It is, after all, only two days. And within those two days, the actions recorded revolve around stress and sorrow, they focus on the distant past, on the family. The cost is that the reader is left with only a very narrow picture of my father.

I Sat With Him On Our Covered Front Porch During A Thunderstorm

My father laughed frequently, filling the house often with his shouts of joy, or a boisterous slap on the dining table. He had a voracious curiosity and read widely. While he loved ideas, and sat reading for hours, he was also a man of action. He’d wanted to be an engineer, a dream from which he was diverted by a math education disrupted by wartime. Still, the impulse to use his hands, to solve technical problems of whatever sort, played out in his prolific vegetable garden, the result of careful study of soil conditioning and plant cultivation. It played out in the sculptures he and I made together. We’d take scraps of wood, paint them black, hammer in irregular but carefully laid out patterns of nails, and then run old telephone wire of varying solid and striped colors from nail to nail, producing delightful geometric creations. It played out in the way he mastered subjects like sailing and nautical navigation (which did make it into the book) and weather. I remember how as a young boy I sat with him on our covered front porch during a thunder storm and he taught me how the timing of lightning and thunder told the story of a storm’s course. I did not fear thunderstorms after that, and would often join him on the bench on the porch and watch the green-gray Maryland sky as it emptied water on the yard in torrents, waiting for the flash, then counting up to the explosion of thunder, and then repeating with the next. I never felt safer. Yet the man in the memoir is not this man – boisterous, curious, confident. The man who loved to take photographs, the brilliant if sometimes cynical political analyst, the dedicated friend. The full man.

Truth and Justice

I do believe that, at its best, memoir has greater power to represent people or circumstances than any other art form. This is what people mean when they refer to the “emotional truth” of memoir. Emotional truth sounds like a weasel-word, a way of wriggling out of actual truth-truth. What I think it means is the truth that is seen by the light that emotion casts on people and events. This meaning holds up in practice again and again.

While I do believe that Finding Maria succeeds, that it tells emotional truth, and as a writer I feel good about that, I am left troubled out here in the real world. People who knew my father may be as much confounded by the mere slice of him that is in the book as they are fascinated by it. People who did not know him, people in the future, his great grandchildren perhaps, may think in gross error that this slice of man was the whole man.

To those who knew him, I hope you can see the man in the book as a character, and try to enjoy the story. To those who did not, I guess I would say that I wish you could have known my father. Take from the book, at least, the experience of his bear hugs. They will tell you much of what you need to know. Imagine how those hugs might wrap you completely and squeeze you just tightly enough to feel uninhibited warmth and love – how the scratch of his whiskers, prickly by late-afternoon, add to the feeling. Sometimes the hugs end with a sighed “Oh, God,” as if he lives the moment in parallel to experiencing it, appreciating, savoring its meaning and beauty. That was my father.

I think the book tells a powerful emotional truth. Yet, in making use of only a small part of a man to help build this truth, I did not fully serve another great end, the cause of justice. As a writer, I am content. As a son, this is the ultimate truth with which I still wrestle.

Buy the book, Finding Maria (Bloomingdale Press – 2nd edition November 25, 2019), on Amazon